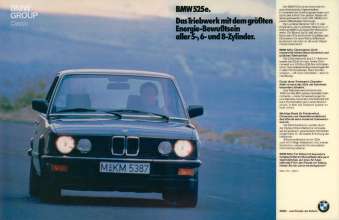

Never has fuel consumption been a topic of such heated debate as during the 1970s. The oil crisis and driving bans brought matters to a head, and concerns about emissions and the environment added fuel to the fire (so to speak). With maximising power no longer the top priority, development engineers searched frantically for new solutions to respond to the sudden craving for efficiency. The “efficiency-enhanced BMW petrol engine” astonished the motoring world, although it didn’t actually make its production debut until 1983 in the E28 BMW 525e.

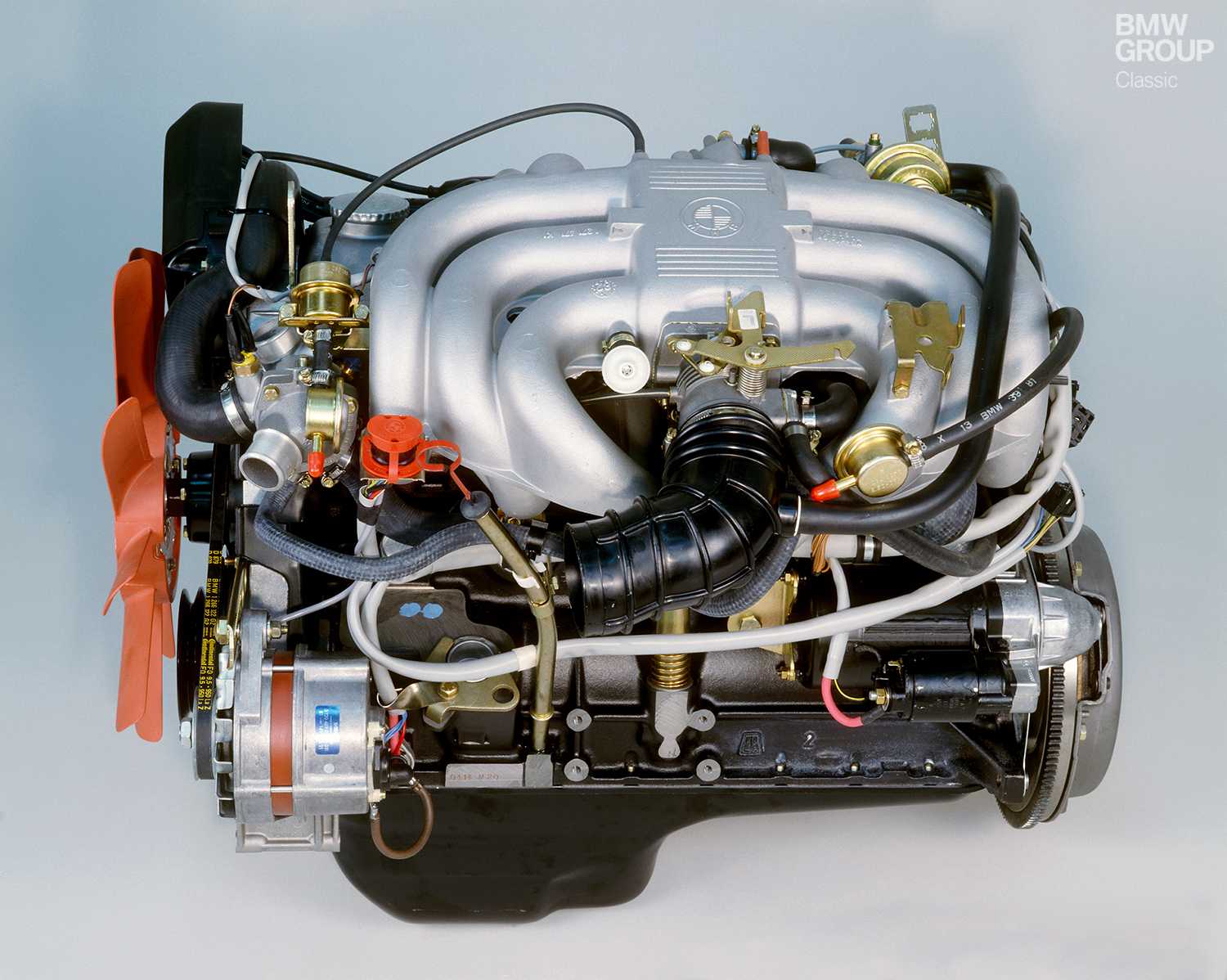

The ‘e’ stood for the Greek letter ‘eta’ denoting energy efficiency, i.e. the ratio between energy used and useful work achieved. In other words, the engine obtained more output from its input. To achieve this, the BMW engineers came up with a wealth of ideas, ranging from altering the shape of the combustion chambers to reducing mechanical friction losses. But perhaps even more importantly, the straight-six engine under the bonnet of the BMW 525e – with displacement increased to 2.7 litres – combined relatively low output with formidable torque from low revs. So formidable, in fact, that the hastiest of drivers switched to a more relaxed driving style almost instinctively. More efficient driving ahoy!

Two very different siblings: the BMW 520i and BMW 525e.

The maximum speed and acceleration times for the BMW 520i and BMW 525e were identical. The factory figures quoted just over eleven seconds for the 0 – 100 km/h (62 mph) sprint and a top speed of around 185 km/h (115 mph). The output of both models was nearly the same, too: 125 hp in the BMW 520i played 122 hp at first, then 125 and finally 129 hp in the BMW 525e. Given the almost total absence of visual differences between them, you could be forgiven for questioning the point of their co-existence. That only became clear out on the road. Whereas the BMW 520i required a far higher engine speed for its peak torque – a whole 4,500 rpm was needed to relay the maximum 165 Nm (122 lb-ft) to the rear wheels – the ‘eta’ variant mustered a mighty 240 Nm (177 lb-ft) from a lowly 3,250 rpm. Such vast reserves of torque were beyond even the turbocharged BMW 524td diesel and only the BMW 528i, whose 184 hp placed it in a completely different power class, was able to get on terms. It was this effortless low-down pulling power that gave the ‘eta’ such tremendous, standout appeal. At the time, BMW’s advertising dubbed it the ideal car for an “engaged yet composed driving style”.

The new ‘e’ approach.

The BMW 525e saved one to two litres of fuel per 100 kilometres over the BMW 520i, depending on driving style. Customers had to be prepared to change their way of thinking, though. Previously, the only thing that mattered was the principle of performance stating that more horsepower and more revs equalled more prestige. Hence the first BMW 525e was accompanied by a major advertising campaign detailing the new way of the world. Not the unusual marketing approach perhaps, but one prompted by experience gained in the USA. Here, customers had initially struggled to get their heads around the BMW 528e launched in 1981, which employed the same principle. This was odd, as it made the perfect match for the strictly regulated roads in the US where, even today, long-distance comfort is the name of the game and maximum speed is purely hypothetical.

The BMW 525e made its debut in 1983 and remained in production until 1987 as a highly attractive member of the model range. Today, it is still regarded as a powerful, well resolved sedan for the connoisseur. The engine made a reappearance a short time later in the smaller E30 3 Series range (as the BMW 325e), where it once again proved to be a beautifully balanced unit. Then came the 1990s, when the modern diesel engine finally established itself as a power merchant offering unbeatable economy that was also ideal for upmarket mid-size sedans. The principle of the ‘eta’ engine had nevertheless been a success; indeed, it can be considered a direct precursor to today’s efficiency-enhanced concepts and their pursuit of ever more output from their input.