They were young and mostly unknown. And they looked like students on their way to a march, all shaggy hair, tight jeans and mildly self-satisfied perma-grins. But behind the façade was heart and fighting spirit to spare, and every member of the squad was quite certain about where they wanted to go: to the top of the podium, knocking the racing establishment off their perch en route. Fast forward to the Belgian Grand Prix circuit at Zolder on a damp and chilly March day in 1977. The scene was set for the BMW Junior Team’s debut race – and nothing would be quite the same again.

The touring car success story

The BMW 3.0 CSL Coupe was the dominant force in European touring car racing in the 1970s. Legendary drivers like Hans-Joachim Stuck got behind the wheel of the distinctively-striped 400-horsepower machines to win race after race. But Jochen Neerpasch, Head of BMW Motorsport GmbH since 1972, wanted more. Neerpasch had devised a programme for up-and-coming young drivers that would unearth and develop talented youngsters and newcomers long before the old guard departed the scene and left a gaping chasm behind them to fill.

The forceful voice of youth.

1977 was the moment when push came to shove; it was time for the BMW Junior Team to sample the bright lights of elite motor sport. A deliberate policy of hand-picking the drivers for the programme from various countries saw the German Manfred Winkelhock joined by Switzerland’s Marc Surer and Eddie Cheever from the US. Cheever was the youngest of the intake at 19, but the others were not much older. Awaiting them was a batch of BMW 320s newly modified to meet Group 5 regulations, but things didn’t get off to the best of starts in Zolder. Cheever, for example, binned his 320 in practice. So when the starter’s flag dropped for the first time, the American was sitting in the spare car.

A record-breaking crowd of 25,000 had flocked to this opening round of the German Racing Championship. And they were treated to a debut performance from another planet, Surer starting from pole and storming to a sensational victory. Winkelhock crossed the line third to join his team-mate on the podium and Cheever – the teenager with the cheeky-scamp face and fresh legacy of twisted metal – was not far behind, having battled his way up to fifth in the spare car. Ford’s motor sport boss Mike Kranefuss had seen enough to predict some gloves-off scraps to come. After all, the top dogs in the championship up to that point were not about to stand aside and let someone else (especially “Neerpasch’s playgroup“, as the new crop were dismissed in some quarters) claim all the glory.

The show and the showdown.

The Nürburgring was the venue for the fledgling team’s second race. Back in those days, that meant the Nordschleife, the modern-day Formula One circuit not joining the complex until 1984. To the excitement of the spectators – but the consternation of the rest of the field – BMW’s young guns once again showed little respect for their established rivals. Famously only ever photographed in a helmet or Tyrolean hat, Hans Heyer mumbled something about the trio not being “right in the head” and Ronnie Peterson labelled them “completely crazy”. Jochen Neerpasch was forced to take his young charges aside and calm them down. And, for a while at least, there was an outbreak of peace.

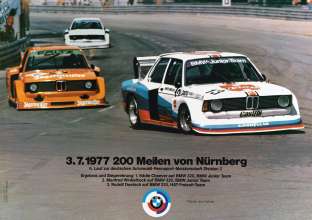

The success, though, kept on coming, with at least two BMW Junior Team drivers on the podium at each of the races leading up to the round of the championship in Nuremberg. Marc Surer was able to sustain his excellent start to the series and arrived at the Norisring second in the standings.

The fast and the furious & fast.

The scene at the Norisring could be summed up in three words: summer, sun and spectators – one-hundred thousand of them. And Porsche had joined the fray for the occasion with a small turbocharged two-litre machine. Walter Röhrl raced into an early lead in his Schnitzer 2002 Turbo, before Cheever fought his way to the front. Hans Heyer and Winkelhock, meanwhile, were engaged in their own private scrap for second place. Emerging from an unscheduled pit stop, Surer slotted back onto the track just behind Cheever and ahead of Heyer and Winkelhock. A memorable tussle ensued, in which no quarter was asked or given and contact was never far away. Surer eventually had to concede defeat and trailed home back in eighth. The Swiss driver’s Junior Team colleagues finished first and second, though, and Heyer – fêted as a hero by the spectators at the finish – was fourth in what remained of his Ford Escort. It had been a rough-and-tumble race of drama and controversy, and the resulting media storm took several days to dissipate.

When heroes need a break.

The tricky job of defusing the situation fell to team boss Neerpasch, who had little choice but to remove his “shock and awe” brigade from combat. Indeed, next time out the BMW 320s were back in the hands of seasoned Formula One drivers Hans-Joachim Stuck, Ronnie Peterson and David Hobbs. Although the 320 was again the race winner, only Stuck lived up to his reputation, taking the victory with something to spare.

Away from the track, there was clearly a desire to make an example of the newly branded “bad boy” Surer. The Swiss driver was called before a sports tribunal, banned for two months and stripped of all his championship points. However, there was still time before the judgement came into force for one last outing at Hockenheim. There, the three juniors took up where they had left off, gung-ho style in rude health. The spectators could hardly contain themselves as the young BMW drivers locked horns with all-comers on the track, saving their finest combat for each other. The German, the Swiss and the American stormed through the corners and down the straights two or – if the occasion demanded – even three abreast, and put on a remarkable show. There were constant changes of position until Cheever finally elbowed Surer off the track, leaving Winkelhock to emerge with the in-house bragging rights.

As the curtain fell on the 1977 season, it was clear that – with the youthful enthusiasm dialled down a little – the new BMW Junior Team could have won all the prizes. Even so, Winkelhock topped the points rankings in the “kleine Klasse” and was third overall, while Cheever and the freshly pardoned Surer finished equal on points in 5th.

Giving those kids a chance.

With the inception of the BMW Junior Team, Jochen Neerpasch inserted a new chapter into the motor sport history books. It took a great deal of nerve and resolve to give this young band of rough diamonds such a rare opportunity, but his decision has been more than vindicated by the passage of time. The German Racing Championship also benefitted, its popularity subsequently reaching uncharted heights. All three drivers soon secured themselves seats in Formula One – Cheever in 1978, Surer in 1979 and Winkelhock in 1982.

The BMW Junior Team laid the foundations for the company’s enduring commitment to junior development, a tradition which continues to flourish to this day. Only with a little more serenity and decorum.